The History of San Francisco’s Mt. Davidson Park

When I first moved to San Francisco in 1980, I was excited to find a tiny home on the slopes of the City’s highest hill. Just steps from my door to the park at its peak is the opportunity to be totally surrounded by a tall forest – a world away from the hubbub of the surrounding city. Time does not stand still and I have been amazed at how this unknown part of San Francisco has since been a focus of some who live elsewhere and want to change it. The inspiration for the book I wrote years ago was to remind us of why this gem came to be.

When I first moved to San Francisco in 1980, I was excited to find a tiny home on the slopes of the City’s highest hill. Just steps from my door to the park at its peak is the opportunity to be totally surrounded by a tall forest – a world away from the hubbub of the surrounding city. Time does not stand still and I have been amazed at how this unknown part of San Francisco has since been a focus of some who live elsewhere and want to change it. The inspiration for the book I wrote years ago was to remind us of why this gem came to be.

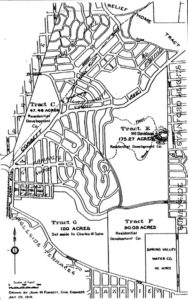

Don Jose de Jesus Noe was the first owner of what we now call Mt. Davidson Park when it was part of a 4443-acre land grant by Mexican Governor Pio Pico in 1845. After California’s statehood in 1850, Noe’s cattle grazing Rancho San Miguel changed ownership several times, but the City’s highest hill remained relatively unchanged until German immigrant, Adolph Sutro, stopped mining the original Mt. Davidson in Nevada. Solving the ventilation and drainage problems with a five-mile tunnel into the silver-rich Comstock Lode made Sutro and his partners multi-millionaires. One of his first investments in 1881 was 1400 acres of Rancho San Miguel. At the urging of the poet, Joaquin Miller (one of the first to promote preservation of the Sierra Nevada forests), Sutro gave school children and the unemployed tree seedlings to plant on his land in celebration of the first Arbor Days. Sutro believed that the planting of trees and hiking in the forests they created would improve the mental and physical health of his fellow residents. (The east side of the is park treeless because it was owned by Leland Stanford). Sutro willed his original 1,400 acres (including the western slope of Mt. Davidson) to an educational trust so his forest land would be preserved for public recreation, but some of his heirs convinced the California Supreme Court to invalidate the will. They sold 700 acres to housing developer, A.S. Baldwin, for $1.4 million in 1911. Baldwin funded the building of a hiking trail to the top of “his” forested side of Mt. Davidson “for the pleasure of the public,” as part of his development advertisment plan.

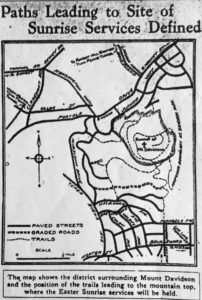

Over a decade later, however, the San Francisco Chronicle proclaimed “Mt. Davidson Unknown to S.F. Citizens.” The hilltop’s obscurity would change after Western Union official James Decatur took up that hiking invitation in 1923 and wrote about the experience: “As the group found themselves deeper in the wood … peace and quiet were so profound that it seemed almost unbelievable that the noise and roar of a great city was only a few minutes behind them … The solitude of the forest … conveyed a sense of vastness quite as real as one would experience among the age-old monarchs of the High Sierras …The undergrowth and flowers looked as if they might have been there for centuries … Decatur got Baldwin’s permission to organize an Easter Sunrise Ceremony atop Mt. Davidson on April 1, 1923. With over 5000 hiking there before dawn to hear the Dean of Grace Cathedral, Decatur and Baldwin decided to make it an annual event.

Attending the ceremony three years later, Mrs. Edmund N. “Madie” Brown, was also inspired – for a different reason. She wanted to put a stop to “the subdivider’s axe and steam shovel from destroying in ruthless fashion the beauties of nature on our beloved Mt. Davidson.” The Federation of Women’s Clubs joined forces with her “to preserve for San Francisco this wooded hill, Mt. Davidson, which will serve to provide our school children with the environment for nature study, the Boy Scouts with an outdoor playground for hikes and overnight camping, the Easter pilgrim with a place of worship on its summit at dawn, and the visitor with unsurpassed views from the highest point in the city.” Prominent citizens were interviewed, letters were written to individuals and organizations asking for their support, and publicity was secured through press and movie newsreels.

An editorial in the April 26, 1927 San Francisco Examiner supported City purchase of the land: “As the residential area advances, the forest goes down before the axe. In another year, it will be too late for the beauty of the summit to be preserved …” Three days later, a report to the Finance Committee of the Board of Supervisors recommended purchase of the summit of Mount Davidson “for a public park serving the needs of the West of Twin Peaks District and also serving as a recreation center and forest playground for the whole city. The acquisition will also preserve for all time the beautiful tree covered slopes of the mountain as an attractive scenic land mark in the city …”

The sum of $15,000 was approved to purchase the first 20 acres in 1927 with the support of Mayor Rolph and the first woman elected to the Board of Supervisors, Margaret M. Morgan. The park was dedicated on the 84th birthday of Park Superintendent John McLaren in 1929 with a plaque honoring Madie Brown: “who found beauty in flower and tree on this lofty hill. Through her untiring pleas, these acres have been set aside as a city park that all may enjoy their beauty and find refreshment of the soul.”

Attendance at the annual Easter Sunrise event skyrocketed to 30,000 by 1932, but nearby housing sales were slowing during the Great Depression. Fundraising began to build a permanent cross on Mt. Davidson, with the help of the developers and builders of the adjoining neighborhoods. The developer’s widow, Mrs. A.S. Baldwin, donated six more acres to the City park for the cross site. The architect of the city’s tallest buildings, George Kelham, was recruited to design the City’s highest monument on it’s highest hill. Built with $20,000 in donations, it took 30,000 feet of lumber to form the 750 cubic yards of concrete that covers 30 tons of reinforced steel. The foundation goes down 16 feet into solid rock. The 103 foot high cross faces due east. It is 10 feet wide at the base and tapers to 9 feet wide at the top. A time capsule under the granite slab at the base contains a copy of the deed of Rancho San Miguel to Don Jose Noe.

Park founder, Madie Brown, asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to dedicate it in 1934:

“As chairman of arrangements, I have dared to dream that you would press a button in Washington, D.C., which in turn would light for the first time this giant cross in San Francisco at its dedication on March 24. It seems most appropriate that you, who have brought light to many a darkened American home and who through your New Deal has instilled the principles of the Golden Rule into American business, should take part in this cross-lighting ceremony.”

President Roosevelt pressed a golden-keyed telegraph switch to light the cross at 7:30 PM before a crowd of 50,000. The cross was lit two weeks a year, thereafter, for Christmas and Easter.

During the remainder of the Depression and through the early 1940s, CBS Radio broadcast the sunrise services coast-to-coast. Seven acres were added to the east side of the park in 1941, as up to 75,000 attended the Easter events during World War II. More acres on the south side were added to the park in in 1950 as housing was built higher up the hill. After a soldier bound for the Korean War wrote of it being his last sight of home, funds were raised to light the cross year-round. Visible from 75 miles away, the twelve 1000-watt lights were turned off in 1976, except during Easter and Christmas weeks, because of the energy crisis. Live television broadcast of the sunrise ceremony began in 1977.

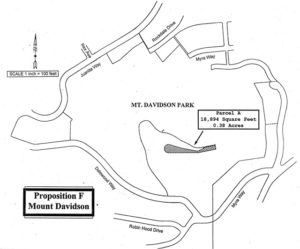

After the lighting of the Golden Gate Bridge was expanded in 1987, fundraising began to resume year-round lighting and obtain historic designation of the cross. However, in response to complaints that public ownership of a religious landmark was a violation of the separation of church and state, the city restricted the lighting to two hours before Easter sunrise. A subsequent lawsuit took ownership of Mt. Davidson to the California Supreme Court a second time. After losing a five-year battle, the city decided to sell the park land under the cross at a public auction to the highest bidder, rather than remove the monument. Neighborhood leaders formed the Friends of Mt. Davidson Conservancy to reduce the amount of park land to be sold to settle the lawsuit. They negotiated limitation of the public park property sale from 6 acres to .38 acre, with deed restrictions ensuring public access and protection of the open space in perpetuity. San Francisco voters approved sale of the park land to the Council of Armenian Organizations of Northern California in November of 1997. The historic lights turned on by President Roosevelt were removed, but portable lighting is allowed two days a year.

Also in 1997, the Recreation and Park Dept. changed the purpose of Mt. Davidson Park from recreation to propagation of native plants as part of the Natural Areas Program. In fulfillment of this mission, their plan to replace the middle third of the forest (10 acres) with shrubs and limit public access throughout the park will be implemented as funding becomes available.

Despite its popularity for huge civic events during the 20th century, two trips to the CA Supreme Court, debates over its landscape, and an significant increase in the city’s density, San Francisco’s highest hilltop park quietly remains as a peaceful forest oasis thanks to the philanthropy of Adolph Sutro and Madie Brown – as if frozen in time since a 1923 newspaper article entitled Mt. Davidson Unknown to SF Citizens exclaimed:

“Once on the way you might imagine yourself in the wildest part of California. The woods appear vast and silent. There is no sign of life along the way. And yet you are still in a city of over 600,000 inhabitants and on every side below you are thousands of closely built homes. No other city in the world offers such a contrast. “

Posted March 5, 2019